Firearms Owners Against Crime

Institute for Legal, Legislative and Educational Action

Institute for Legal, Legislative and Educational Action

There has been some attention given yesterday and today about a study coming out from the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University:

Repeal of Missouri’s background check law associated with increase in state’s murders

Missouri’s 2007 repeal of its permit-to-purchase (PTP) handgun law, which required all handgun purchasers to obtain a license verifying that they have passed a background check, contributed to a sixteen percent increase in Missouri’s murder rate, according to a new study from researchers with the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research.

The study, to be published in a forthcoming issue of Journal of Urban Health, finds that the law’s repeal was associated with an additional 55 to 63 murders per year in Missouri between 2008 and 2012. State-level murder data for the time period 1999-2012 were collected and analyzed from the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) system. The analyses controlled for changes in policing, incarceration, burglaries, unemployment, poverty, and other state laws adopted during the study period that could affect violent crime. . . . .

The study has gotten breathless coverage from Jonathan Amos at the BBC, Robert VerBruggen with Real Clear Policy, Julia Dahl at CBS, Chelsea Coatney at the PBS Newshour, Steve Benen at MSNBC, and Niraj Chokshi at the Washington Post. The staid Roll Call has a headline “Study Shows Gun Control Works.” Others such as Piers Morgan tweeted about it.

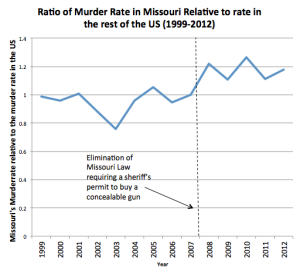

Bottom line: There are a lot of problems with how the tests here are conducted, particularly cherry picking one state when many states have these laws, but even if one accepts the way all those decisions were made, the change in murder rates don’t change what people think that they do. The results are more complicated than simply looking at what the average murder rate before and after rescinding the Missouri law. While it is true that the murder rates in Missouri rose 17 percent relative to the rest of the US after the law was changed, it had actually increased by 32 percent during the five years prior to the change. The question is why the Missouri murder rate was increasing relative to the rest of the US at a slower rate after the change in the law than it did prior to it. The period 1999 to 2012 is picked because that is the period of time examined in Webster’s study. The data is Missouri is available here and for the US here. The US data was net of the numbers for Missouri.

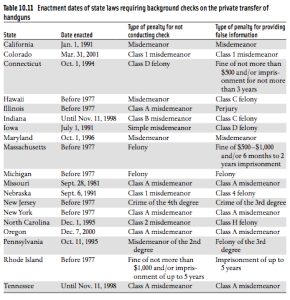

More detailed discussion on how to do empirical tests: You can’t do a study like this on one state over time. There are 17 states with “universal background checks” (see table below for laws up through beginning of 2007). You can’t just pick one state. Let me give you an example. You flip a coin 20 times — ten heads and ten tails. If you specifically picked just five heads from the sample, could you conclude that the coin was biased? Presumably not. There is research on these universal background checks across all the states. Indeed, the third edition of More Guns, Less Crime provided one study on this, and, unlike the Webster study, it shows no benefit in terms of murder rates from these laws. The question the media should ask is: why pick one state when there are so many states with this law? Not only isn’t it the right way to do research, it is pretty obvious to anyone who has looked at the national data that Webster picked that one state to report because it was the one that gave him the result that he wanted. Do studies that collect data on every state take a little more time? Sure, but it isn’t that much more difficult and without it you can’t really determine anything.

Note that the results from More Guns, Less Crime show a slight 2 percent increase in murder rates from “universal background checks,” but the result was not statistically significant.

It is problematic to look at one state for another reason. It is essentially impossible to disentangle all the changes that are occurring on when you are looking at only one experiment. Take another example that has been hotly debated: the Supreme Court’s 1963 Miranda decision requiring that defendants have to be read their rights. Some claim that decision increased crime rates during the 1960s because it made it harder to convict criminals, but there is no way we can really tell. For example, during that term there were three other Supreme Court decisions just on crime issues. All one knows is that the crime rate when up after the decision, but you can’t even tell if it was the Miranda decision or one of the other cases that was responsible, let alone all the other changes that were occurring at that time. The point of using national data, as was used in More Guns, Less Crime, is that by using lots of different states that change their laws in lots of different years you can begin to disentangle these different effects. Unfortunately, you can’t do that with the Miranda ruling because all states were changed in the same way at the same time. With the current research only looking at Missouri, you are producing biased estimates because you are not able to properly disentangle all the changes that were occurring in Missouri.

Other questions are why the paper only examines murder rates and not any other type of violent crime or why only murder rates from 1999 and later are examined. Again, the answer is clear: none of the other violent crime rates, including robbery, showed the change that Webster desired. As to the years studied, one would think that since Missouri’s law went into effect in 1981 researchers would study the impact on crime both when the law was adopted and when it was repealed. Yet, again, the answer for why this wasn’t done is obvious.

For those interested, More Guns, Less Crime also has information on licensing. If you would want to play the game of pointing to one state on the other side of the issue, see Massachusetts for an example (see also here).